“If someone tells you writing is easy, he is either lying or I hate him.” —Farley Mowat

Tuesday, December 1, 2015

"'This is a title for a post on Metafiction,' Title-man said, calling attention to the mechanics of writing," she cleverly entitled this post on Metafiction.

Once upon a time there was a blogpost which began, "once upon a time there was a blogpost which began by speaking about metafiction," Gary Barwin, the author of this blogpost wrote on this blog seeking to demonstrate some metafictional strategies in the very discussion of metafiction. "Clever, eh?" he thought. "Yes," Gary said. "Very." Internet readers everywhere rolled their eyes. One at a time. A wave of single eyes rolling, like R's, across the entire world. Now, Jorge Luis Borges appears. Non-sequiturially like in a Donald Bartheleme story.

Ahem.

This is a famous metafictional children's story. No, not this. The this below. Down there.

The Monster at the End of this Book

This is also another one which uses a whole meta-ton of metafictional techniques and is also very funny. The Stinky Cheese Man and other stories.

And now, the dialogue begins:

"Some metafictional strategies to try," she said. "Since I seem to be here as if I am a real character speaking in real dialogue. Oh look at the font I speak in. It's classic. BTW, what happens to me when you stop reading? When I stop talking? When you click to another webpage? When the sun explodes? When I decide to only THINK these thoughts and not have them written down for me?"

"Ok. So she's gone. So, Dear Reader, (Yeah, your webcam is active. Surprise!) Write using one ore more of the following metafictional strategies," No-one said. Ever.

a. Reverse traditional narrative processes. Reverse the expected order of cause and effect. Or Make a story unfold via a non-normative structure. Footnotes. A list. A collection of artifacts (e.g. Jon Paul Fiorentino's The Report Cards of Leslie Mackie, a story made out of report cards.) Or model a story after a dictionary. (Milorad Pavić's The Dictionary of the Khazars.) Or comprised of footnotes (e.g. Nabokov's Pale Fire which purports to be a long poem with scholarly annotations but is really the story of the author and the footnoter told from the very biased perspective of the man writing the footnotes.)

b. Make a list of punning/allusive names that telegraph a character's traits and purpose in a story. Use them in fun combinations, allowing the names to dictate the story's shape. Generally use destabilizing or self-conscious names, some kind of obvious organization. Cf. Black, Blue, etc. in Paul Auster’s Ghosts. Or all the same letter, or alphabetical. Maybe objects or places in the story are organized by letter, or some other quality which makes the reader aware of their formal or arbitrary nature.

c. Pepper a story with a symbol that means many things, or nothing. Or one incongruous thing, like a dove that symbolizes violence, or a paper kite that symbolizes imprisonment.

Experiment with point of view (rewrite a famous story—real or fictional, from the perspective of a different character than the normative one. The POV character could even be a non-human or inanimate object Be self- reflexive and have the character comment on the process of writing. Feel free to insert the author as a POV character.

eg. The Titanic story from the Iceberg’s perspective (cf. Billy Bragg’s great song which does this) or Beowulf from Grendel’s POV (in John Gardner’s Grendel,) Wizard of Oz from the witch’s POV (Gregory Maguire’s Wicked.)

d. Include anachronisms. Old things in the modern day. Vice versa. Future things.

e. Dialogue: dialogue with no statements or with no questions, or using surprising or unexpected tone, language, etc.

f. Break the fourth wall. Address the reader. Make yourself (as yourself or in the role of the writer) a character. Be self conscious about the “fictiveness” or “storyness” of the story and its components. (eg. Six Characters in Search of an Author, Slaughterhouse Five.) Make the story or book a character. Or refer to it in the story or book. (E.g. If on a Winter’s Night a Traveller.) Also:

g. The characters know they are in a story. The story refers to itself. The story is a story within a story. (Cf. Hamlet, Rosenkrantz & Guidenstern are Dead, Don Quixote, Slaughterhouse Five.)

h. Retell a well known story or historical fact in a different way. Counterfiction: i.e. What if such and such didn’t or did happen. Michael Chabon's Yiddish Policemen’s Union, bpNichol's The True Eventual Story of Billy the Kid.

Thomas King retells stories from an indigenous perspective (e.g. A Coyote Columbus Story--this is from one of his short story collections.) Here's a nice presentation about it. There's an illustrated picturebook version, too.

What if there was something different about a historical character. They are gay. Their gender is switched. They have a secret. Or…?

i. Frame story fun: he told me this story that once upon a time there was a boy who wrote a story about a boy who cried wolf.

Write a story within a story. Within a story.

WHY do all of this?

Gnatola ma no kpon sia, eyenabe adelan to kpo mi sena. (Ewe-mina)

Until the lion has his or her own storyteller, the hunter will always have the best part of the story. (English)

Satire. Humour. Critical analysis of received wisdom or knowledge. A “looking under the hood,” or a revealing of the strings and puppetmaster in the puppet act. A examination of how we are manipulated or how we respond to elements in story.

A reframing of the current perspective taking into account different perspectives. (Indigenous, queer, feminist, alternate political perspectives, etc. )

Are we are fictional constructs, perhaps created by the narrative of our situation, language, culture, etc. How can we see through this?

Is truth/story/received knowledge reliable, true, or even knowable? Is truth quantum and is changed by our attempts at its observation or articulation? Can we trust language and normative language structures?

_______________

Appropriation or plundering or stealing is another useful technique. And the author of this post, Goldilocks Threebears, has done that too, taking many of these exercises in some form or other from here but none from here or here.

BTW did you see that strange formating on the possessive appostrophe S in Pavic's name? So destabilizing, it makes you wonder if all language is just made up. Like, I mean, how come all those kids in France are so good at speaking French? It's taken me years just to be able to sprachen de French even a little bit. Eh, Wittgenstein? Stop pretending to be so dead and answer me.

And this. Write a metafiction incorporating this gif.

Wednesday, November 25, 2015

Novel Whispering: Planning, Motivation, and....uh I just can't finish this heading....

Writing on a Tread Desk

The Plot Whisperer

WRITE OR DIE SOFTWARE: "putting the 'prod' in production."

Wednesday, November 18, 2015

On Setting

1. SOUNDBATH.

What is a setting actually like? What tells us what it's like.

Have half the class makes a soundscape based on a location (hospital emergency room, or a primary classroom, or a highway, etc.) while the other half the class writes through what they hear. The kicker: the sounders keep it a secret what location they're sounding.

2. PERCEPTION CHANGES SETTINGS

CHOOSE ONE:

from John Gardner’s The Art of Fiction

4a. Describe a landscape as seen by an old woman whose disgusting and detestable old husband has just died. Do not mention the husband or death.

4b. Describe a lake as seen by a young man who has just committed murder. Do not mention the murder.

4c. Describe a landscape as seen by a bird. Do not mention the bird.

4d. Describe a building as seen by a man whose son has just been killed in a war. Do not mention the son, war, death, or the old man doing the seeing; then describe the same building, in the same weather and at the same time of day, as seen by a happy lover. Do not mention love or the loved one.

3. CHARACOMBISETTINGERCISE

On small pieces of blank paper, each person should write one of two types of info (one type of info per piece of paper): a) LOCATION where a story might occur and b) CHARACTER (real or fictional). Make sure you keep you piles of LOCATIONS separate from your piles of CHARACTERS. After 3 minutes of speed-brainstorming/writing, our whole class will combine ALL locations in a pile, and then ALL characters in a separate pile. Mix thoroughly. Everyone then chooses 1 location and 2 characters. Finally, spend 10-15 minutes writing a scene set in that location, where those two characters meet. Read & discuss.

Wednesday, November 11, 2015

It's to Dialogue For

from Roddy Doyle’s Two Pints

-What’s culture, an’anyway?

-Wha’?

-Culture – what is it, like? Exactly.

-I don’t fuckin’ know. Opera an’ bukes. Tha’ sort o’ shite.

-Not accordin’ to my missis.

-What’s she say it is?

-Well – there was a yoke on the radio, abou’ Dublin applyin’ for the European City o’ Culture an’ tha’. An’ I said, ‘A load o’ bollix’.

-Spot on.

-No.

-No?

-She tore the face off me. She’s been doin’ an Open University thing – with her sister. Annyway. D’yeh know wha’ she says?

-Wha’?

-We’re culture.

-Wha’ – us?

-Me an’ you – yeah.

-How did she come up with tha’?

-Well – accordin’ to her, like – it’s the way we talk, our use of the vernacular –

-The fucks an’ tha’.

-Exactly. She says tha’ me an’ you are a perfect example of the city’s livin’, vibratin’ culture. An’ somethin’ else as well. Yeah – we’re improv theatre at its most extreme.

-What’s tha’ mean?

-Haven’t a clue. But I put in an application.

-For wha’?

-For me an’ you to be included in the programme.

-Where?

-Here.

-In the fuckin’ pub?

-Eight performances a night, seven nights a week, for all o’ 2020. Except Good Friday an’ Christmas Day.

-Doin’ wha’?

-Wha’ we always do. Talkin’ shite, drinkin’, goin’ to the jacks, scratchin’ our arses.

-Would it not be borin’?

-It’s supposed to be. Culture – it’s supposed to be borin’. Good for yeh.

-Like vegetables.

-Exactly.

-What’s culture, an’anyway?

-Wha’?

-Culture – what is it, like? Exactly.

-I don’t fuckin’ know. Opera an’ bukes. Tha’ sort o’ shite.

-Not accordin’ to my missis.

-What’s she say it is?

-Well – there was a yoke on the radio, abou’ Dublin applyin’ for the European City o’ Culture an’ tha’. An’ I said, ‘A load o’ bollix’.

-Spot on.

-No.

-No?

-She tore the face off me. She’s been doin’ an Open University thing – with her sister. Annyway. D’yeh know wha’ she says?

-Wha’?

-We’re culture.

-Wha’ – us?

-Me an’ you – yeah.

-How did she come up with tha’?

-Well – accordin’ to her, like – it’s the way we talk, our use of the vernacular –

-The fucks an’ tha’.

-Exactly. She says tha’ me an’ you are a perfect example of the city’s livin’, vibratin’ culture. An’ somethin’ else as well. Yeah – we’re improv theatre at its most extreme.

-What’s tha’ mean?

-Haven’t a clue. But I put in an application.

-For wha’?

-For me an’ you to be included in the programme.

-Where?

-Here.

-In the fuckin’ pub?

-Eight performances a night, seven nights a week, for all o’ 2020. Except Good Friday an’ Christmas Day.

-Doin’ wha’?

-Wha’ we always do. Talkin’ shite, drinkin’, goin’ to the jacks, scratchin’ our arses.

-Would it not be borin’?

-It’s supposed to be. Culture – it’s supposed to be borin’. Good for yeh.

-Like vegetables.

-Exactly.

*

Mostly Obvious, but Bears Repeating.

some notes stolen from YA writer Ellen Jackson.

"What is the use of a book without pictures or conversation?" --Alice (from Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll)

SIX FUNCTIONS OF DIALOGUE

Dialogue reveals character.

"Show the little runt around the mansion," said Mr. Grisly, "and then feed him to the piranhas."

Dialogue gives necessary information.

"That’s my cat," Missy told the fireman. "She’s been missing for days. Her name is Patches."

Dialogue moves the plot along.

"I’m going to the store, and when I come back you’d better have your homework done," said Mom.

Dialogue can show what one character thinks of another character.

"You stay here and brood about the meaning of life," said Chester. "I’ll take care of Patsy."

Dialogue can reveal conflict and build tension.

"You’ve got the smarts to get into medical school," said Dad.

"But I’ve always wanted to be a teacher," said Megan.

"Nonsense," said Dad. "You’ll change your mind."

Dialogue can show how someone feels.

"What’s the matter with you?" asked Jose. "I’ve never known you to snap like that."

"So what? Who cares?" said Rita. "You haven’t even called to see how my sister’s doing."

WRITING CAPTIVATING CONVERSATIONS

A person gets to know a character in the same way that he gets to know a real person–through her speech and behavior. For this reason, the first rule for writing effective dialogue is to make it sound real.

After you’ve written a few lines, always read what you’ve written aloud. You’ll spot mistakes and cliches that you wouldn’t otherwise notice, and you can tell whether you’ve written dialogue that feels natural and authentic. Also, note the rhythm and pacing of your writing. Is the tension increasing? Is one character getting angrier? Are the two characters in agreement or in conflict with one another?

Well-written dialogue consists of four elements.

1. The words each character speaks.

2. The tags, or words such as "he says" or "she asked" that indicate the speaker.

3. The gestures and actions of each character.

4. The underlying emotions of the character.

TEN TIPS FOR WRITING DIALOGUE

1. Good dialogue reflects a character’s age, background, and personality.

A ten-year-old boy doesn’t have the same speech patterns as a forty-year-old woman. Be aware of these differences.

2. Be aware how your character would react in a given situation.

Does your character have a sense of humor? Does he fly off the handle easily? Show these qualities through dialogue.

3. Most people use contractions when they speak.

When children speak they’ll almost always say "you aren’t" instead of "you are not" and "it’s" instead of "it is." Using contractions make your story children’s speech sound more natural.

4. Intersperse your dialogue with body language and action.

Dialogue interspersed with action and gestures helps the reader visualize your characters. But don’t overdo it. Too much action is as distracting and as too little.

5. Don’t allow dialogue to repeat narration.

Avoid this: Madison came in the door. He threw his books on the table and went into the kitchen to get a cookie. "I see you’re home from school," said Mom. "How about a cookie?"

6. Stick with simple tags.

Use ordinary tags such as "he said" or "she asked" almost all of the time. Elaborate tags (queried, questioned, bellowed, stated, replied, responded, pointed out) are distracting and unnecessary.

7. Don’t allow your characters to get too verbose.

Characters who talk too much are boring. Every line of dialogue needs a specific reason for its existence. Keep your story moving and your dialogue spare.

8. Pay attention to the developing relationships among your characters.

People’s feelings toward one another change over time. As your story evolves, the relationships between your characters evolve too and the changes need to be reflected in the dialogue.

9. Listen to real life conversations.

Listen to your friends, neighbors, and family. Take notes and keep a list of the interesting expressions you hear. Real speech can seldom be used verbatim, but it can often be reconstituted as dialogue.

10. Good dialogue has rhythm.

People who are stressed out speak in short, clipped sentences. People who are relaxed speak more expansively and in longer sentences. When you listen to people’s conversations, study the music beneath the words.

http://www.ellenjackson.net/dialogue_61473.htm

LOOKING AT THE DIALOGUE

Dialogue is the actual spoken conversations of the character - the bits found in the quotation marks. Like Alice in Wonderland, many young people will scan the page looking for "conversations" because dialogue shows the story will be about people. The young reader is much more interested in the people and what they do and say than he is in long exposition or lengthy lyrical passages about the weather or color of the clouds. Dialogue is often where we meet the personality of the characters and find the humor of the story.

Although dialogue gives voice to the characters, that cannot be all it does. Dialogue is unbreakably tied to the plot and must be essential to the plot. If two characters ramble on about pansies, pansies must be essential to the plot of the story. It isn't enough that the discussion shows the characters are quiet homebodies, it must also move something forward. Everything in your story must help that forward motion that is the plot. Because of this, the best dialogue is set inside the action of the story. And because of this, editors often look askance at the long passages of lecture-ish dialogue between your main character and a wise adult - these passages often interrupt plot action, bringing the story to a painful halt.

WHAT DIALOGUE IS NOT

Dialogue is also not a way to dump the details on the reader. Dialogue can sneak in details, but never ever dump. For example, this would be bad dialogue:

"What's the matter?" Beth asked. "I haven't seen you this droopy since Dad up and left in the middle of the night last year and we all had to try to figure out how to survive on Mom's bitty income waiting tables at the Awful Waffle."

"Yeah," Bobby said, thoughtfully as he remembered those terrible days of questioning whether he was the reason Dad left. Dad never liked Bobby's interest in books and drawing instead of sports and hunting. "But this is even worse. There's a bully at school who is picking on me. You know how much shorter I am than all the other guys and how I can't seem to put on weight no matter how much I eat. Mom says I'm scrawny as a plucked chicken. How can I deal with a bully who is twice my size?"

That kind of dialogue is marked by characters telling each other things they already know for the sake of the reader. Kids aren't fooled by that. They know it's fake and thus it pushes them away from the characters instead of making the story more emotionally real. That doesn't mean you can't sneak in hints about the past:

Beth walked over and plunked down beside Bobby. "So, what's the matter this time?"

Bobby glared at her. Sure, he hadn't been Mister Jolly the past year without Dad but Beth acted like all he did was mope like a little kid. "Nothing."

"Right," she said. "This wouldn't have anything to do with that bruise on your cheek would it?"

Bobby's hand flew to his face. "It shows? Mom's going to freak."

"When Mom gets home, she's too tired to see, much less freak."

Maybe, but Bobby didn't like to take the chance.

Notice how it covers much of the same ground but does it a bit more subtly and puts things to see in front of the reader as well. That helps distract from a little "informing" and makes it more natural and palatable. So, whenever you need to get the reader up to speed - be sneaky.

_____________

(The “game” begins around 2’30”)

This is a picture of a plaque which commemorates an interaction, followed by an awkward silence. I wonder where else plaques marking awkward silences might be placed. What was the conversation/situation that resulted in the awkward silence?

3. Write a dialogue between two or more people which incorporates information about the history of the poppy as a symbol. Here's some info.

Here's a cartoon that does this:

4. What I did for breakfast: TWO HAVE A CONVERSATION

-two people transcribe what the others say.

-then switch.

OBSERVE HOW PEOPLE ACTUALLY SPEAK

now edit. what do you leave out.

how could you make this exciting.

-what if there was a knock on the door and an alien was there.

continue conversation as if this happened and include Alien.

5. The scenario: Two people have been becoming friends for a while. One of them needs to tell the other a secret (can be good or bad), but knows she/he can’t just blurt it out. So what do they say?

[Decide who you are and what the secret it. Now edit.]

6. Write a scene in which one person tells another person a story. Make sure that you write it as a dialog and not just a first person narrative, but clearly have one person telling the story and the other person listening and asking questions or making comments. The purpose of this scene will be both to have the story stand alone as a subject, and to have the characters’ reactions to the story be the focal point of the scene.

7. Write a scene in which one person is listening to two other people have an argument or discussion. For example, a child listening to her parents argue about money. Have the third character narrate the argument and explain what is going on, but have the other two provide the entire dialog. It is not necessary to have the narrator understand the argument completely. Miscommunication is a major aspect of dialog.

8. Write a conversation between two liars. Give everything they say a double or triple meaning. Never state or indicate through outside description that these two people are lying. Let the reader figure it out strictly from the dialog. Try not to be obvious, such as having one person accuse the other of lying. That is too easy.

9. Write a conversation in which no character speaks more than three words per line of dialog. Again, avoid crutches such as explaining everything they say through narration. Use your narration to enhance the scene, not explain the dialog.

____________________________________

Sample Characters

movie star and fanatic fan

officer and speeder

psychiatrist and patient

waiter/waitress and diner

man on a ledge and psychologist

principal and student

hairdresser/barber and client

teacher and parent

little sis and big sis

driving instructor and student driver

deejay and phone-in listener

reporter and accident witness

priest and confessor

cheerleader and nerd

girl and boy on blind date

dogcatcher and dog owner

player and coach

two late-night grocery shoppers

girl's date and little brother or sister

flight attendant and passenger

man and God

angel and devil on character's shoulder

Wednesday, November 4, 2015

Introducing Characters to the Reader

Introducing Characters to the Reader

a. telling it directly

Mr Maurice Smith was something of a snob.

b. allowing the character to tell it.

I am much more discerning than I used to be, Smith thought. Though I suppose I’ve become a bit of a snob in the process.

c. allowing some other character to express it.

“Don’t waste your time on him,” Jane Roberts said to her younger sister. “Maury Smith has no time for the likes of us any more.”

d. letting the character’s actions suggest it.

When Smith turned the corner, he discovered the source of the shouting. A demonstration. Labourers in hard hats wielded placards. One of the men pushed a pamphlet into Smith’s hands. He dropped it as he might have dropped a handful of steaming dung, and hurried away, glancing to either side in case someone he knew had seen.

Showing Emotions

1. Physical evidence: His heart raced. His palms were damp.

2. Revealing actions: Again he dropped the hat. Once he’d picked it up, he squeezed it and twisted it between his hands.

3. Facial expressions: He closed his eyes quickly, and turned away. His lips, you could see, were moving.

4. Stream of consciousness: I will not let them see, he thought. I will not give them the satisfaction. Let them think I am as courageous as they are.

5. Dialogue responses: “Me?” His voice cracked. “Me? But there must be…I can’t do…Excuse me, I’d better sit down.”

6. Projection onto setting. The room, when he entered, was crammed with people buzzing with contentment at one another’s company. All turned, and leveled gazes at him that said: And what right do you have to come amongst us?

7. Metaphor: Why did he feel, whenever she turned that lion-sized smile on him, that he’d been mistaken for a Christian?

8. Allusion: For a moment he felt himself to be a trembling Faustus, about to cry out a pleas for a merciful postponement.

9. Rhythm: No, he would not. He would not. He would refuse. He would grit his teeth and smile till his lips bled. He would never, never, never let them see.

10 Sympathetic language: Perhaps the curtains flutter nervously, or the walls sweat condensation; perhaps the people bray when they laugh, growl when they suggest, bully when they persuade, or rear back, as though about to charge him.

Characterization through actions and movement.

Even single words—verbs—can change the whole feel of a sentence:

Megan opened the door to the classroom and walked to the teacher's desk

Megan opened the door to the classroom and tiptoed to the teacher's desk.

Megan opened the door to the classroom and crawled to the teacher's desk.

Megan opened the door to the classroom and flew to the teacher's desk.

Megan opened the door to the classroom and stumbled to the teacher's desk.

Megan yanked open the door to the classroom and scrambled to the teacher’s desk.

Dialogue

How does your character talk? What markers (emotional, regional, class, etc) in their speech note their character? How do they interact with others?

adapted from Barbara Haworth-Attard, & Jack Hodgins,

adapted from Barbara Haworth-Attard, & Jack Hodgins,

TWO CHARACTER TYPOLOGIES FROM:

House Mother Normal by B.S. Johnson

Thursday, October 29, 2015

ASSIGNMENT, CLASS 5 (OCTOBER 28)

¶ + ¶

Two paragraphs-ish

Please write:

1. What is the MAIN WORK of your novel (or idea for a novel) is. What changes in the main character and their world? What would you say the major conflict or issue being unfolded or confronted? (See the one before the previous post—"Plot and Structure: The Mountain" for diagrams of structure and for guides to types of conflict, issues, and subject.)

This isn’t to be a synopsis (though some elements of plot will necessarily enter into your discussion.) What

2. How do you imagine that the novel will be told – i.e. what structure and why did you choose it? Include something about POV if that seems important.

Please complete this for next class. You can either email to me or hand in a hard copy.

Two paragraphs-ish

Please write:

1. What is the MAIN WORK of your novel (or idea for a novel) is. What changes in the main character and their world? What would you say the major conflict or issue being unfolded or confronted? (See the one before the previous post—"Plot and Structure: The Mountain" for diagrams of structure and for guides to types of conflict, issues, and subject.)

This isn’t to be a synopsis (though some elements of plot will necessarily enter into your discussion.) What

2. How do you imagine that the novel will be told – i.e. what structure and why did you choose it? Include something about POV if that seems important.

Please complete this for next class. You can either email to me or hand in a hard copy.

Wednesday, October 28, 2015

Name and other things Generator

Check this out!!!! (Look under "generator types")

This is a great site for not only finding the listed kinds of nouns, but by mixing and matching, or riffing off what they suggest, you can find great new material & ideas.

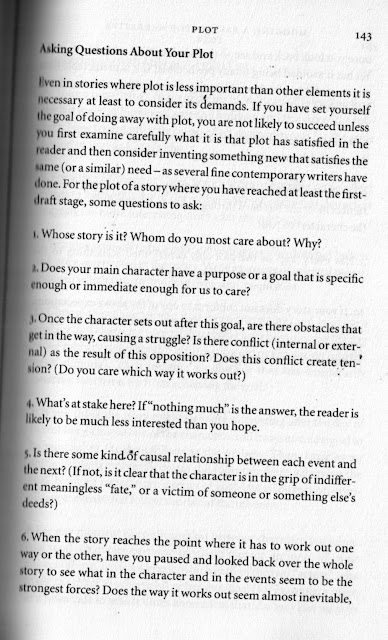

Plot & Structure: The Mountain

The Paris Review: Mapping Plot

Crazy plot diagramming of TV shows.

Norman Friedman: The Theory of the Novel

Plots of Fortune

The Action plot – what happens next

The Pathetic Plot – sympathetic protag undergoes misfortune through no fault of her own

The tragic plot—sympathetic protag who has strength of will & ability to change his thought “suffers from a misfortune, part of all of which he is responsible for…and subsequently discovers his error too late

The Punitive Plot—a protag who is unsympathetic gets his due

Sentimental Plot – sympathetic protag survives the threat of misfortune and comes out all right at the end

Admiration Plot – our final response is respect and admiration for man outdoing himself and the expectations of others concerning what man is normally capable of

Plots of Character

The Maturing Plot—a sympathetic but apparently purposeless protag achieves strength and direction

The reform plot—we feel impatience & irritation when seeing through a sympathetic protag’s mask and then indignation when he continues to deceive others and then finally a sense of

The testing plot—protag pressured to compromise or surrender his noble ends and habits

The degenerative plot – sympathetic & ambitious protag is subject to crucial loss and falls apart

Plots of Thought

Education plot—sympathetic protag undergoes a threat of some sort and emerges into a new and better kind of wholeness in the end

The Revelation plot—protag must discover the truth of his situation before he can come to a decision

The Affective plot—the protag comes to see some other person in a truer light than before

The Disillusionment plot – a sympathetic and idealistic protag after being subjected to some kind of loss, threat or trial, loses that faith entirely

The Thick Plottens: Simple approaches to plot

THE THICK PLOTTENS

A story's plot is what happens in the story and the order it happens in.

For there to be story, something has to move, to change. Something goes from point A to point B.

This change could be:

• A physical event (Point A = psycho killer is picking off everyone in town. Point B = police arrest the killer).

• A decision (Point A = character wants to practice law like his father. Point B = character decides to be a ballet dancer).

• A change in a relationship (Point A = They hate each other. Point B = They fall in love)

• A change in a person (Point A = character is a selfish jerk. Point B = character has learned to be less of a selfish jerk.)

• A change in the reader's understanding of a situation. (Point A = character appears to be a murderer. Point B = The reader realizes that character is actually innocent and made a false confession.)

This change could even be the realization that nothing will ever change. (Point A = your character dreams of escaping her small town. Point B = her dream escape is shown to be an hopeless.)

What is plot?

It's the road map that takes your story from point A to point B.

Happiness is overrated

Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.

– Tolstoy, Anna Karenina

There's a reason why "Happily ever after" comes at the story's end. It means nothing else is happening. Cinderella and her Prince Charming wake up late, eat a nice breakfast, and take a walk. A slow news day. Forever.

It would be different if it were: "Happily ever after, except for one extramarital affair and its violent ending..." "Happily ever after until Cinderella discovered Prince Charming's secret dungeon..."

There’s nothing wrong with happiness. There's just no story in it.

The story is how you get to the happy ending. Or how it turns sour.

For there to be a story, something's got to happen. Narrative conflict is what makes it happen. This can be:

• a conflict between characters (Prince Charming's ex-girlfriend decides to break up the marriage)

• a character's internal conflict (Cinderella develops a drinking problem)

• a conflict between characters and an impersonal force (floods, disease, dragon attacks)

Einstein once said, "Nothing happens until something moves." If your characters are getting comfortable too early in the story, it's time to stir things up.

How to stir up major trouble

How do you come up with an interesting conflict for your story? It's often a good idea to start with your main character.

• What's something this character desperately wants? What difficulties might get in the way? There's your conflict.

• What would force this character to do something he or she is really uncomfortable with? Something he or she doesn't feel capable of doing? Create this situation, and you've got a conflict.

Or maybe there's a specific type of conflict you feel inspired to write about, and you're building your story from there. Perhaps you already know that you want to write about divorce or a battle with cancer or child abuse. That's fine, but be careful not to skimp on character development. Remember that the more real you can make your character for readers, the more deeply readers will care what happens to him or her. We lose sleep worrying over the divorces and illnesses of our friends, not those of strangers.

DRAWING your road map

Okay, so you've invented characters, and you've planned a conflict that will get them off their sofa and doing something interesting. How to organize your story?

Here's a traditional way of looking plot structure:

Step 1) The reader gets to know your characters and to understand the conflict. You can accomplish this by showing instead of telling. How? Illustrate their character/personality without telling. Prince Charming finds an insect on his throne. He calls his manservant to flick it off for him while calling “Ewwww!” Or he puts it on the ground and grinds it into the floor, noting the satisfying crunching sound. Or, he puts the insect into Cinderella’s décolletage and laughs a little squeally a laugh. Or he gently places the insect outside the window and says, “Be free, small one.” And then he notes the satisfying crunching sound as he grinds his manservant beneath his foot.

Step 2) You build up the conflict to a crisis point, where things just can't continue the way they are. A decision has to be made or something has to change. This point is called the story climax. If the story is a road map, this is the major fork in the road.

The character can turn left and wind up in Alabama with her ex-lover or turn right and end up back in Illinois with her husband and kids.

The story climax is when Cinderella discovers Prince Charming's dungeon. Will she leave? Will she just pretend she doesn't know? The rest of the story depends on what happens at this moment. The story climax can be a moment of great suspense for your reader. It determines how the story will end, the location of Point B.

Step 3) Show, or hint at, Point B. This is called the story's resolution, and it all depends on how the climax played out.

Remember that this is just one theory of plot structure. But it provides a road map that will give your reader an interesting ride from Point A to Point B. Then, as you read and write more and more short fiction, you will develop your own sense of the best shape for each story.

*

A story's plot is what happens in the story and the order it happens in.

For there to be story, something has to move, to change. Something goes from point A to point B.

This change could be:

• A physical event (Point A = psycho killer is picking off everyone in town. Point B = police arrest the killer).

• A decision (Point A = character wants to practice law like his father. Point B = character decides to be a ballet dancer).

• A change in a relationship (Point A = They hate each other. Point B = They fall in love)

• A change in a person (Point A = character is a selfish jerk. Point B = character has learned to be less of a selfish jerk.)

• A change in the reader's understanding of a situation. (Point A = character appears to be a murderer. Point B = The reader realizes that character is actually innocent and made a false confession.)

This change could even be the realization that nothing will ever change. (Point A = your character dreams of escaping her small town. Point B = her dream escape is shown to be an hopeless.)

What is plot?

It's the road map that takes your story from point A to point B.

Happiness is overrated

Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.

– Tolstoy, Anna Karenina

There's a reason why "Happily ever after" comes at the story's end. It means nothing else is happening. Cinderella and her Prince Charming wake up late, eat a nice breakfast, and take a walk. A slow news day. Forever.

It would be different if it were: "Happily ever after, except for one extramarital affair and its violent ending..." "Happily ever after until Cinderella discovered Prince Charming's secret dungeon..."

There’s nothing wrong with happiness. There's just no story in it.

The story is how you get to the happy ending. Or how it turns sour.

For there to be a story, something's got to happen. Narrative conflict is what makes it happen. This can be:

• a conflict between characters (Prince Charming's ex-girlfriend decides to break up the marriage)

• a character's internal conflict (Cinderella develops a drinking problem)

• a conflict between characters and an impersonal force (floods, disease, dragon attacks)

Einstein once said, "Nothing happens until something moves." If your characters are getting comfortable too early in the story, it's time to stir things up.

How to stir up major trouble

How do you come up with an interesting conflict for your story? It's often a good idea to start with your main character.

• What's something this character desperately wants? What difficulties might get in the way? There's your conflict.

• What would force this character to do something he or she is really uncomfortable with? Something he or she doesn't feel capable of doing? Create this situation, and you've got a conflict.

Or maybe there's a specific type of conflict you feel inspired to write about, and you're building your story from there. Perhaps you already know that you want to write about divorce or a battle with cancer or child abuse. That's fine, but be careful not to skimp on character development. Remember that the more real you can make your character for readers, the more deeply readers will care what happens to him or her. We lose sleep worrying over the divorces and illnesses of our friends, not those of strangers.

DRAWING your road map

Okay, so you've invented characters, and you've planned a conflict that will get them off their sofa and doing something interesting. How to organize your story?

Here's a traditional way of looking plot structure:

Step 1) The reader gets to know your characters and to understand the conflict. You can accomplish this by showing instead of telling. How? Illustrate their character/personality without telling. Prince Charming finds an insect on his throne. He calls his manservant to flick it off for him while calling “Ewwww!” Or he puts it on the ground and grinds it into the floor, noting the satisfying crunching sound. Or, he puts the insect into Cinderella’s décolletage and laughs a little squeally a laugh. Or he gently places the insect outside the window and says, “Be free, small one.” And then he notes the satisfying crunching sound as he grinds his manservant beneath his foot.

Step 2) You build up the conflict to a crisis point, where things just can't continue the way they are. A decision has to be made or something has to change. This point is called the story climax. If the story is a road map, this is the major fork in the road.

The character can turn left and wind up in Alabama with her ex-lover or turn right and end up back in Illinois with her husband and kids.

The story climax is when Cinderella discovers Prince Charming's dungeon. Will she leave? Will she just pretend she doesn't know? The rest of the story depends on what happens at this moment. The story climax can be a moment of great suspense for your reader. It determines how the story will end, the location of Point B.

Step 3) Show, or hint at, Point B. This is called the story's resolution, and it all depends on how the climax played out.

Remember that this is just one theory of plot structure. But it provides a road map that will give your reader an interesting ride from Point A to Point B. Then, as you read and write more and more short fiction, you will develop your own sense of the best shape for each story.

*

25 Ways to Plot

25 WAYS TO PLOT, PLAN AND PREP YOUR STORY

from terrible minds

http://terribleminds.com/ramble/2011/09/14/25-ways-to-plot-plan-and-prep-your-story/

by Chuck Wendig (novelist, screenwriter, and game designer)

1. THE BASIC VANILLA TRIED-AND-TRUE OUTLINE

The basic and essential outline. Numbers, Roman numerals, letters. Items in order. Separated out by section if need be (say, Act I, Act II, Act III). Easy-peazy Lyme-diseasey.

2. THE REVERSE OUTLINE

Start at the end, instead. Write it down. “Sir Pimdrip Chicory of Bath slays the dragon-badger, but not before the dragon-badger bites the head off Chicory’s one true love, Lady Miss Wermathette Kildare of the Manchester Kildares.” Rewind the clock. Reverse the gears. Find out how you build to that.

3. TENTPOLE MOMENTS

A story in your head may require certain keystone events to be part of the plot. “Betty-Sue must get sucked into the time portal outside Schenectady, because that’s why her ex-boyfriend Booboo begins to build a time machine in earnest which will accidentally unravel space-and-time.” You might have five, maybe ten of these. Write them down. These are the elements that, were they not included, the plot would fall down (like a tent without its poles). The narrative space between the tentpoles is uncharted territory.

4. BEGINNING, MIDDLE, END

Write three paragraphs, each detailing the rough three acts found in every story: the inciting incident and outcome of the beginning (Act I), the escalation and conflict in the middle (Act II), the climactic culmination of events and the ease-down denoument of the end (Act III). You can, if you want, choose the elemental changes-in-state you might find at the end of each act, too — the pivot point on which the story shifts. This document probably isn’t more than a page’s worth of wordsmithy. Simple and elegant.

5. A SERIES OF SEQUENCES

The saying goes that an average screenplay usually offers up eight or nine sequences (a sequence being a series of scenes that add together to form common narrative purpose, like, say, the Attack On The Death Star sequence from Star Wars). So, chart the sequences that will go into your screenplay. If you’re writing prose, I don’t know how many sequences a novel should have — more than a film, probably (or alternately, each sequence is granted a greater conglomeration of scenes).

6. CHAPTER-BY-CHAPTER

For novel writers, you can chart your story by its chapters. A standard outline is more about dictating plot and story without marrying oneself to narrative structure. This, however, puts the ring on that finger and locks it down tight. A chapter-by-chapter outline is visualizing the reader’s way through the novel.

7. BEAT SHEET

This one’s for you real granular-types, the ones who want to count each grain of sand on your story’s beach. Chart each beat of the story in every scene. This is you writing the entire story’s plot out, but you’re writing it without much dialogue or narrative flair. It’s you laying out all the pieces. The order-of-operations made plain.

8. MIND-MAPS

Happy blocks and bubbles connected to winding bendy spokes connected to a central topical hub. Behold: example. You can use a mind-map to chart… well, anything your mind so desires. It is, after all, a map of said mind. Sequence of events? Character arcs? Exploration of theme? Story-world ideas? Family trees? The crazy hats worn by your villains? Catchphrases? Your inchoate rage and shame made manifest? Your call.

9. ZERO DRAFT

AKA, “The Vomit Draft.” Puke up the story. Just yarf it up — bleaaarrghsputter. A big ol’ Technicolor yawn. You aren’t aiming for structure. Aren’t aiming for art or even craft. This is just you getting everything onto the page so that it’s out there and can now be cleaned up. You’ve puked up the story, now it’s time to form it into little idols and totems — the heretic statuaries of your story.

10. IN THE DOCUMENT, AS YOU GO

AKA, “The Bring Your Flashlight” technique. You outline only as you go. Write a scene or chapter. Roughly sketch the next. Then write it. Onward and upward until you’ve got a proper story.

11. WRITE A SCRIPT

For those of you writing scripts, this sounds absurd. “He wants me to outline my script by writing a script? Has this guy been licking colorful toads?” Sorry, screenwriters — this one ain’t for you. Novelists, however, will find use in writing a script to get them through the plotting. Scripts are lean and mean: description, dialogue, description, dialogue. It’ll get you through the story fast — then you translate into prose.

12. DIALOGUE PASS

Let the characters talk, and nothing else. Put those squirrely fuckers in a room, lock the door, and let the story unfold. It won’t stay that way, of course. You’ll need to add… well, all the meat to the bones. But it’s a good way to put the characters forward and find their voice and discover their stories. Remember: dialogue reads fast and so it tends to write fast, too. Dialogue is like Astroglide: it lubricates the tale.

13. CHARACTER ARCS

Characters often have arcs — they start at A, go to B, end at C (with added steps if you’re feeling particularly saucy). Commander Jim starts at “gruff and loyal soldier boy in the war against the Ant People” (A) and heads to “is crippled and betrayed by his country, left to die in the distant hills of the Ant Planet” (B) and ends up at “falls in love with a young Ant Maiden and he must fight to protect his ant-man larvae” (C). A character arc can track plotty bits, emotional shifts, outfit changes, whatever.

14. SYNOPSIS FIRST

You might think to write your query letter, treatment or synopsis last. Bzzt. Wrong move, donkeyface. Write it up front. It’s not etched in stone, but it’ll give you a good idea of how to stay on target with this story.

15. INDEX CARDS

Index cards are a kick-ass organization tool. You can use them to do anything — list characters, track scenes, list chapters, identify emotional shifts, make little Origami throwing stars that will give your neighbors wicked-ass paper-cuts. Lay them on a table or pin ‘em to a corkboard. Might I recommend John August’s “10 Hints For Index Cards?” I might, rabbit. I might. See also: the Index Card app for iOS.

16. WHITEBOARD

A whiteboard represents a great thinking space. Notes, mind-maps, character sketches, drawings of weird alien penises. Get some different color pens, chart your story in whatever way feels most appropriate.

17. THE CRAZY PERSON’S NOTEBOOK

Once in a while a story of mine demands a hyper-psycho notebook experience. My handwriting is messier than a garbage disposal choked with hair, but even still, sometimes I just like to put pen to paper and scribble. And I sometimes print stuff out, chop it up, and tape it into the notebook.

18. COLLAGE

You’re like, “What’s next? A shoebox diorama of the Lincoln assassination?” That’s a different blog post. Seriously, on my YA-cornpunk novel POPCORN, I took a whole corkboard and covered it in images and quotes that were relevant to the work. Then I’d just wander over there from time to time, stare at it, get my head around the story I’m telling and the feel of the world the story portrays. Surprisingly helpful.

19. SPREADSHEETS

Stare too long into the grid of a spreadsheet and you will feel your soul entangled there — a dolphin caught in a tuna net. Even still, you may find a spreadsheet very helpful. Track plots and beats to your heart’s delight. Seen JK Rowling’s spreadsheet for Harry Potter?

20. STORY BIBLE

Everything and anything goes into the story bible. Worldbuilding. Character descriptions. The “rules” of the story. Plot. Theme. Mood. An IKEA furniture manual. (Goddamn Allen wrenches.) The BIOSHOCK story bible was reputedly a 400+ page beast, which means that yes, your story bible may be bigger than your actual novel. The key is not to let this — or any planning technique — become an exercise in procrastination. You plan. Then you do. That’s the only way this works.

21. THE POWER OF TEMPLATES

Film and TV scripts already follow a fairly rigorous template, but you can go further afield. Look to Blake Snyder’s SAVE THE CAT beats. Or Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey. Go weirder with the Proppian morphology of fairy tales. You may think it non-imaginative but the power of art and story lives easily within such borders as it does outside of them.

22. STREAM OF CONSCIOUSNESS STORY BABBLE

Slap on a diving bell and jump deep into the waters of the stream of consciousness. Order, you see, is sometimes born first from chaos, wriggling free from a uterus made from fractal swirls and Kamikaze squirrels. Open yourself to All The Frequencies: get into your word processor or find a blank notebook page and just scribble wantonly without regard to sense or quality. You may find your story lives in the noise and madness and that on that snowy screen you will find structure. Like a Magic Eye painting that reveals the image of a dolphin riding a motorbike and shooting Japanese whalers with twin chattering Uzis.

23. VISUAL STORYBOARDS

Sometimes the words only come when given the bolstered boost of a visual hook. Sketch it out yourself. Get an artist friend. Find images from the Internet. Ingest some kind of dew-slick jungle mushroom and paint your story on the wall in an array of bodily fluids. Sometimes you really need to visualize the story.

24. THE TEST DRIVE

Take your characters, storyworld and ideas, and run them through a totally separate story. Let’s call it apocryphal, or “non-canonical.” It’s not a story you intend to keep. Not a story you want to publish. You’re just taking your story elements through their paces. Run them around a test drive. “This is where Detective Shirtless McGoggins solves the murder of the goblin seamstress.” Sure, your Detective lives in the real world, a world not populated by goblins. Fuck it, it’s just an exercise. A test run to find his voice and yours.

25. PANTS THE HELL OUT OF IT

All this plotting and scheming just isn’t working for you, so go ahead and pants the hell out of it. (Me? I don’t wear pants. Pants are the first tool of your oppressors.) Sometimes trying to wrestle your story into even the biggest box is just an exercise in frustration, so do what works for you and what doesn’t. Once again, however, I’ll exhort you to at least learn the skill of outlining — because eventually, someone’s going to ask for a demonstration of your ability.

Monday, October 26, 2015

Wednesday, October 21, 2015

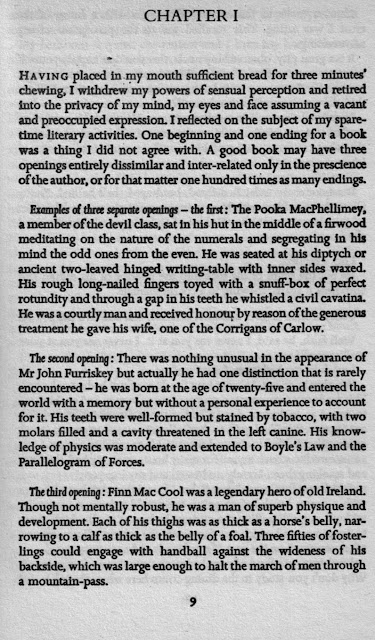

Three great novel beginnings: Flann O'Brien.

Sunday, October 11, 2015

If you've been added, you can ADD A NEW POST wherein you post

your writing

[It will show up on the main page, but that's ok. Please label your post like this:

GARY BARWIN: The Most Remarkable First Chapter (Oct 11), though of course, you'd use your own details, unless you want the exhilarating thrill of pretending to be me and my writing. If so, let me know and I'll send my utilities bills your way, also. Thanks!

[It will show up on the main page, but that's ok. Please label your post like this:

GARY BARWIN: The Most Remarkable First Chapter (Oct 11), though of course, you'd use your own details, unless you want the exhilarating thrill of pretending to be me and my writing. If so, let me know and I'll send my utilities bills your way, also. Thanks!

Tuesday, October 6, 2015

The 31 Functions of Vladimir Propp

The 31 Functions of Vladimir Propp

After the initial situation is depicted, the tale takes the following sequence of 31 functions:

1. ABSENTATION: A member of a family leaves the security of the home environment. This may be the hero or some other member of the family that the hero will later need to rescue. This division of the cohesive family injects initial tension into the storyline. The hero may also be introduced here, often being shown as an ordinary person.

2. INTERDICTION: An interdiction is addressed to the hero ('don't go there', 'don't do this'). The hero is warned against some action (given an 'interdiction').

3. VIOLATION of INTERDICTION. The interdiction is violated (villain enters the tale). This generally proves to be a bad move and the villain enters the story, although not necessarily confronting the hero. Perhaps they are just a lurking presence or perhaps they attack the family whilst the hero is away.

4. RECONNAISSANCE: The villain makes an attempt at reconnaissance (either villain tries to find the children/jewels etc.; or intended victim questions the villain). The villain (often in disguise) makes an active attempt at seeking information, for example searching for something valuable or trying to actively capture someone. They may speak with a member of the family who innocently divulges information. They may also seek to meet the hero, perhaps knowing already the hero is special in some way.

5. DELIVERY: The villain gains information about the victim. The villain's seeking now pays off and he or she now acquires some form of information, often about the hero or victim. Other information can be gained, for example about a map or treasure location.

6. TRICKERY: The villain attempts to deceive the victim to take possession of victim or victim's belongings (trickery; villain disguised, tries to win confidence of victim). The villain now presses further, often using the information gained in seeking to deceive the hero or victim in some way, perhaps appearing in disguise. This may include capture of the victim, getting the hero to give the villain something or persuading them that the villain is actually a friend and thereby gaining collaboration.

7. COMPLICITY: Victim taken in by deception, unwittingly helping the enemy. The trickery of the villain now works and the hero or victim naively acts in a way that helps the villain. This may range from providing the villain with something (perhaps a map or magical weapon) to actively working against good people (perhaps the villain has persuaded the hero that these other people are actually bad).

8. VILLAINY or LACK: Villain causes harm/injury to family member (by abduction, theft of magical agent, spoiling crops, plunders in other forms, causes a disappearance, expels someone, casts spell on someone, substitutes child etc., commits murder, imprisons/detains someone, threatens forced marriage, provides nightly torments); Alternatively, a member of family lacks something or desires something (magical potion etc.). There are two options for this function, either or both of which may appear in the story. In the first option, the villain causes some kind of harm, for example carrying away a victim or the desired magical object (which must be then be retrieved). In the second option, a sense of lack is identified, for example in the hero's family or within a community, whereby something is identified as lost or something becomes desirable for some reason, for example a magical object that will save people in some way.

9. MEDIATION: Misfortune or lack is made known, (hero is dispatched, hears call for help etc./ alternative is that victimized hero is sent away, freed from imprisonment). The hero now discovers the act of villainy or lack, perhaps finding their family or community devastated or caught up in a state of anguish and woe.

10. BEGINNING COUNTER-ACTION: Seeker agrees to, or decides upon counter-action. The hero now decides to act in a way that will resolve the lack, for example finding a needed magical item, rescuing those who are captured or otherwise defeating the villain. This is a defining moment for the hero as this is the decision that sets the course of future actions and by which a previously ordinary person takes on the mantle of heroism.

11. DEPARTURE: Hero leaves home;

12. FIRST FUNCTION OF THE DONOR: Hero is tested, interrogated, attacked etc., preparing the way for his/her receiving magical agent or helper (donor);

13. HERO'S REACTION: Hero reacts to actions of future donor (withstands/fails the test, frees captive, reconciles disputants, performs service, uses adversary's powers against him);

14. RECEIPT OF A MAGICAL AGENT: Hero acquires use of a magical agent (directly transferred, located, purchased, prepared, spontaneously appears, eaten/drunk, help offered by other characters);

15. GUIDANCE: Hero is transferred, delivered or led to whereabouts of an object of the search;

16. STRUGGLE: Hero and villain join in direct combat;

17. BRANDING: Hero is branded (wounded/marked, receives ring or scarf);

18. VICTORY: Villain is defeated (killed in combat, defeated in contest, killed while asleep, banished);

19. LIQUIDATION: Initial misfortune or lack is resolved (object of search distributed, spell broken, slain person revived, captive freed);

20. RETURN: Hero returns;

21. PURSUIT: Hero is pursued (pursuer tries to kill, eat, undermine the hero);

22. RESCUE: Hero is rescued from pursuit (obstacles delay pursuer, hero hides or is hidden, hero transforms unrecognisably, hero saved from attempt on his/her life);

23. UNRECOGNIZED ARRIVAL: Hero unrecognized, arrives home or in another country;

24. UNFOUNDED CLAIMS: False hero presents unfounded claims;

25. DIFFICULT TASK: Difficult task proposed to the hero (trial by ordeal, riddles, test of strength/endurance, other tasks);

26. SOLUTION: Task is resolved;

27. RECOGNITION: Hero is recognized (by mark, brand, or thing given to him/her);

28. EXPOSURE: False hero or villain is exposed;

29. TRANSFIGURATION: Hero is given a new appearance (is made whole, handsome, new garments etc.);

30. PUNISHMENT: Villain is punished;

31. WEDDING: Hero marries and ascends the throne (is rewarded/promoted).

Occasionally, some of these functions are inverted, as when the hero receives something whilst still at home, the function of a donor occurring early. More often, a function is negated twice, so that it must be repeated three times in Western cultures.[4]

Characters

He also concluded that all the characters could be resolved into 7 broad character functions in the 100 tales he analyzed:

1. The villain — struggles against the hero.

2. The dispatcher — character who makes the lack known and sends the hero off.

3. The (magical) helper — helps the hero in their quest.

4. The princess or prize and her father — the hero deserves her throughout the story but is unable to marry her because of an unfair evil, usually because of the villain. The hero's journey is often ended when he marries the princess, thereby beating the villain.

5. The donor — prepares the hero or gives the hero some magical object.

6. The hero or victim/seeker hero — reacts to the donor, weds the princess.

7. The false hero — takes credit for the hero’s actions or tries to marry the princess.[5]

These roles could sometimes be distributed among various characters, as the hero kills the villain dragon, and the dragon's sisters take on the villainous role of chasing him. Conversely, one character could engage in acts as more than one role, as a father could send his son on the quest and give him a sword, acting as both dispatcher and donor.[6]

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)